Studio Sindone

The new website about the Shroud: a matter of reason, not of faith

A MESSAGE IN CODE FOR THE MAN OF THE 21st CENTURY?

by Antonio Bonelli

The conflict between faith and science, and between faith and reason,

is one of the most amazing swindle of human history.

Summary

- The "history" and its limits in the Shroud affair

- What's the response of "science"? - First Part

- What's the response of "science"? - Second Part

- How had that extraordinary image formed?

- The "affair" of the C14 dating

- Who is the man of the Shroud?

- Discussion

What's the response of "science" - First Part

For more then half a millenium, from its appearance in France and until the treshold ot the XX century, the little we know of the linen, beyond its surface of 4x1 meters, is the human image for which, due to the anatomic features of a dead man and the several signs clearly related with a deadly Passion, it was all the time thought to be the Shroud where Jesus' body had been wrapped by Joseph of Arimatea. A scientific study of the Shroud and its image began only in 1898, when the amateur photographer Secondo Pia photografed it for first time. His already excellent pictures - followed in 1931 by Joseph Enrie's, in 1969 by Judica Cordiglia's and in 1978 by Vernon Miller's, all professionals - gave surprising evidence and details of the anatomic features and signs of Passion. What's more, discovered that the image owns an unexpected and astonishing intrinsic peculiarity. Let's go through the finds in detail.

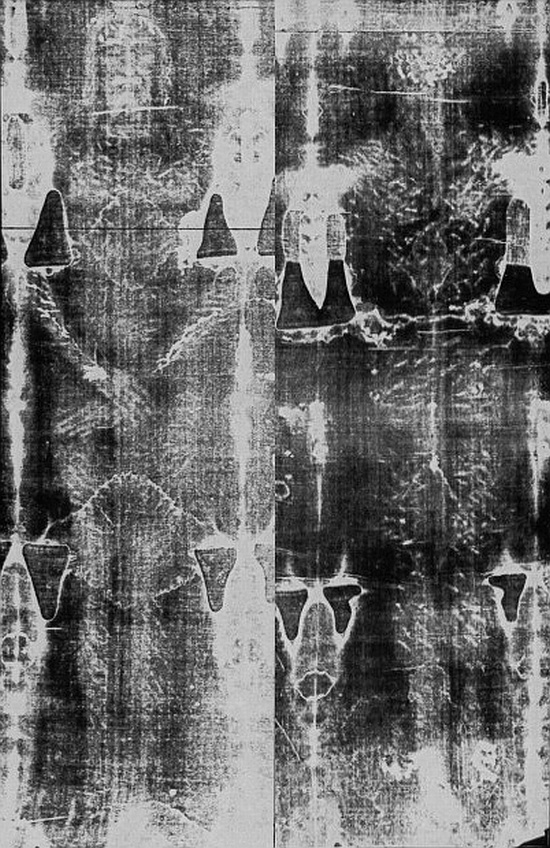

Fig. 2: the Holy Shroud turned into a negative

The anatomic features, refer to a man about forty, lying on his back. The forearms converge to the pubis, the hands overlapped on it. The lower limbs and feet are close each to other and stretched. Thick and long is the hair, plaited along the back. Thick are also moustache and beard.

The signs of Passion are many and significant on both faces of the Shroud. Four large stains looking like wounds, later turned out to be of human blood of AB group(11), mark the right chest(6), the feet and the left wrist (the right one is covered).(7) Countless other wounds and abrasions are spread all over the body. Most of them show a three-point design around a hyphen(8): this suggests the use of the "fragrum" o "flagellum taxillatum" for the flagellation (flogging), and the skin was marked with up-to-down, right-to-left and left-to-right directions, as if two scourgers had been at work. Another large stain is impressed on the forehead, whereas the swollen face hints at contusions.

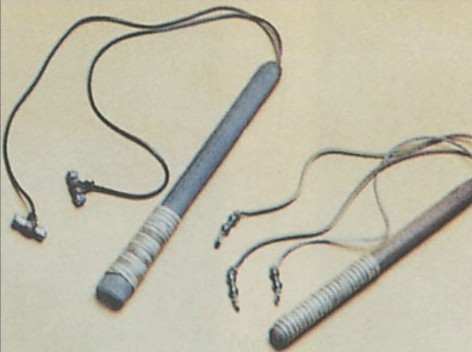

Fig. 2a: the "fragrum" or "flagellum taxillatum" used by Romans

The nose profile is sharp altered as for a fracture:

Fig. 2b: details about cheek and nose

The hands, prone, hide the thumbs.(9)

But the astonishing, intrinsic peculiarity of the image consists in its being a photographic negative.

It was an amazing surprise for all and a disquieting challenge for scientists!

Notes

(6) Due to the specular feature of the image, the sides look inverted.

(7) The nails in the wrist contrast with the millenary iconography of the crucifixion, wherein they are pierced in the middle of the hands. But, as we know today, that was just the procedure used, as the only capable to hold the weight of a suspended body; perforated hands break through. Not a single hypothetical "painter" of the Middle Ages could have been aware of. In this regard, the greek term χειρ (xeir, "hand") means also wrist up to the elbow or the whole arm.

(8) It reproduces the two leads or little bones on the tip of the "flagrum" o "flagellum taxillatum", the scourge used by the Romans for flogging. These signs are fluorescent; that is why some of them are invisible to the naked eye, and revealed only by the light of the Wood lamp.

Fig. 2c: particular of ropes of "fragrum" or "flagellum taxillatum"

(9) It's a fact of forensic medicine interest due to the transfixion of the wrist that, implying the lesion of the medial nerve, causes the thumb to fall behind the palm. Not a single hypothetical "painter" of the Middle Ages would have - as actually no one had - represented the hands with only four fingers.

(11) There is no evidence on the image of pigments, other colouring matters, marks and strokes of the brush, signs of a painting style, so the image isn't a painting. Its extra-soft brownness concerns the fibrils of the threads of warp and weft only on their very surface, so that it's not perceivable on the other side of the linen. The tone of brownness is identical in each and all fibres, what makes the lights and shades depend only on the number of browned fibrils per surface unit. The ensuing imprint has a very soft contrast with the linen, has no points of saturation and its highest optic density is exactly equal on both faces of the cloth. This last property means that the image had formed with no pressure on the Shroud, as clearly confirmed by the posterior aspect of the represented corpse, not at all deformed and flattened as it is the rule for soft tissues undergoing weight.

Heat is by far the most credited cause of the image. Yet, nobody ever succeded in experimentally obtaining by means of heat an image somehow similar to that of the Shroud. Beyond that, the brownness due to heat leaves behind traces of pigments, penetrates deep into the fibrils, marks them with different degrees of saturation and alters them so much, to make it easily visible, especially today, with optic tools and a fluorescent lamp. But about this there is no trace on the surface of Shroud. No better chance of success had and has the "hypothesis light", since the Shroud is all but a photo film, and in the XIV century the camera hadn't been yet invented. The stains, referred to blood by devotion and logic of "design", are actually due to blood, human blood of group AB. The halo spread around some of the largest, like the one on the chest, contains human serum albumins, accounting for its fluoroscence.

The stains, which are the only organic material unrelated to the linen itself, are endowed with the property of thickness, so that it's possible to remove them; but they don't show the signs of fragmentation and partial detachments that crusts usually present on bandages removed from wounds. Contrary to the image, they penetrate deep into the filaments to the point they become visible on the opposite side of the cloth; lastly, they are the only parts of the image that are not in negative, and the fibers beneath them are white rather than burnished. In other words, underneath the blood stains there is no image. The evidence suggests that the image had formed after the deposition of the body and upon the blood stains, without passing them through. Moreover, in correspondence of the bodily orifices there is no sign of decomposition, which shows its effects after about 40 hours from death. Which is why we know that the body remained in the linen for no longer than two days. Even if the body had been touched with the most gentle attention while being removed from the Shroud, or if a number of people had agitatedly purloined it, the blood stains would not have shown such well-defined outlines, but in fact signs of dragging, smudges and detachment of crusts. Wanting to look at the logical conclusion, we really must assume that the body was neither touched nor removed: the Shroud seems emptied from the inside and crossing through the linen, the body is as... vanished. For further elements aiming at excluding human interventions in the shaping of the image see points 7) and 9).