Studio Sindone

The new website about the Shroud: a matter of reason, not of faith

A MESSAGE IN CODE FOR THE MAN OF THE 21st CENTURY?

by Antonio Bonelli

The conflict between faith and science, and between faith and reason,

is one of the most amazing swindle of human history.

Summary

- The "history" and its limits in the Shroud events

- What's the response of "science"? - First Part

- What's the response of "science"? - Second Part

- How had that extraordinary image formed?

- The "affair" of the C14 dating

- Who is the man of the Shroud?

- Discussion

The "history" and its limits in the Shroud events

The presence of the Sacred Shroud in France in 1353 or shortly before, is historically certain, and is also known the itinerary to reach Turin, where it still is.(1) Equally certain is that the Shroud is a mortuary linen cloth where it is impressed the image of a man's corpse showing plagues and signs that exactly match to the ones reported by the Gospels about the Passion of Christ. The same Linen looks surprisingly similar to the one that for many centuries was preserved and exposed to the veneration of worshippers every friday in the church of St. Mary, in the district of Blackern in Constantinople.

Among the illustrious visitors to whom the Byzantine emperors exhibited it between 1171 and 1203 were William, Chancellor of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and archbishop of Tyre, and Almeric the king of Jerusalem. But from Constantinople the Shroud disappeared in that tragic 1204, when the city fell to the Knights of the IV Crusade and was heavily ransacked. Many objects of great devotional and artistic value were then robbed ant taken to Europe by the conquerors as war trophies. Although not historically proved, it's likely that the same fate has befell also by that linen, as the holiest relic of Christendom. Isn't it then possible, that the hrouds of Turin and of Constantinople are the same one? Many and convincing arguments are clearly in favour.(2)

What is known of the precious linen cloth of Constantinople before it appeared in that city? Suggestive is the story of Edessa (the present Turkish town of Urfa), then in Syria and one of the first Christian churches, founded according to the tradition by the disciple Thaddeus.(3) A linen known as the Edessa mandylion (mandilion or mandillon, in greek "μανδύλιoν") and manytime folded up (tetràdiplon, "four times double" according some ancient sources) with the suffering Christ's visage represented on its cover face, would has been brought to Edessa a long time ago and through uncertain ways, in a crossing of legend and tradition which surprisingly they converge.

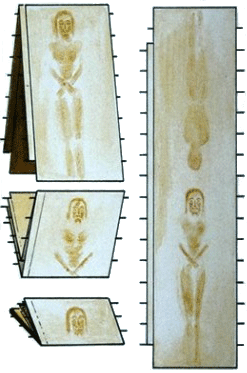

Fig. 1: hypothesis of folding of the Shroud, according the signs of folds that the Shroud shows with regular intervals

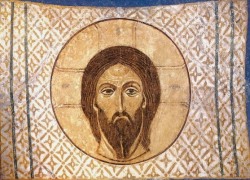

Fig. 1b: fresco of the Mandylion, Monastery of the Transfiguration, Pskov, XIII° century. The vast iconography seems to confirm that the image was preserved in a reliquary with a grate, so as to show only the Face

Perhaps because of persecution, to protect from plunderers and desecrators, the Mandylion was hidden - and probably forgotten for many centuries - in a niche of the city walls and it was found again on VI century.(4) In VII century Edessa fallen to the Muslims and was reconquered from the Arabic by the Byzantine general John Curcas (Kurkas) who got the Mandylion, took it along to Constantinople where he was welcomed by the jubilant crowd. If all this is true, the linen of Edessa, Constantinople and Turin could be considered as the same object with reasonable certainty (Rambaud and Runciman). These historic researches and many others of the kind, still on the way, seem us of great speculative intrest but of very little importance in the end, since bound for nowhere. In fact, should they even conclude that the Turin Shroud already existed at Jesus' times, this would never prove it is really the one cited by the four evangelists.(5) That is why, we confine them in marginal notes. So, we have to go another way through. Indeed, neither history nor faith are able to bring forth that identification. Only science can, scanning throughout the misteries hidden in the linen cloth and the image on it.

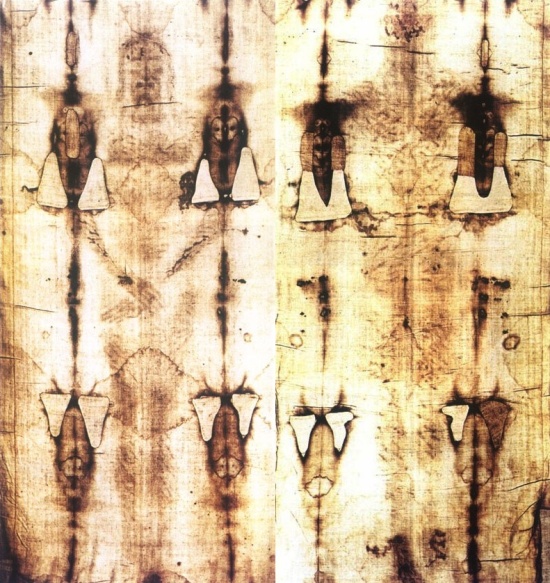

Fig. 1c: the Holy Shroud as we see front and back

Notes

(1) Unknown is how, in 1349, the Shroud became property of King Philip II of France (see also note 2). One year later, on his death-bed, he bequeathed it to his faithful esquire, Geoffrey, the Count of Charny and lord of Lirey, a little village in the Champaigne Region, perhaps in reward for his taking sides in the war against England. So, it is just in the year 1350 that we fix the "official" entry of the Shroud of Turin into history. During the Hundred Years' War, Margaret, the Geoffrey's grand-daughter, took off the Shroud from the canons of Lirey, to whom it had been entrusted, and in order to safeguard it from plunderers and damaging, she put it in safe in her husband's castle. In 1452, she refused to hand it over again to the canons who claimed their rights on it, and sent it to Chambéry to a cousin, Anne, daughter of the king of Cyprus and wife of the Duke of Savoy Louis I.

In 1467 Pope Paul II granted to Duke the permission to build a chapel for the Shroud in his capital-city Chambéry. Between 1472 and 1474 Pope Sistus IV confirmed the privileges with three bulls. On the Holy Saturday of 1503, the Linen was taken to the near town of Bourg-en-Bresse, to be shown to the Archduke Philip le Beux of Austria, there on a trip. Then with the bull Romanus Pontifex in 1506 Pope Julius II allowed the Christians to venerate the Shroud as a holy relic.

Back stadily in Chambéry after several public ostensions throughout France, between 3rd and 4th Dec. 1532 the Shroud was hardly rescued from a fire that destroyed the wooden chapel where it was kept. Due to the flames and the water of extinction, the linen, then twelve times folded on itself in a casket, was only slightly damaged. When inspected stretched out, it disclosed the presence of sixteen large and twelve lesser holes, later mended by the Clares Sisters of that city.

In 1578 the Duke Emmanuel Philibert transfered the Shroud from Chambéry to Turin to shorten as possible the pilgrinage of Milan's Archbishop, Carlo Borromeo, who had vowed to go to France on foot to venerate the Shroud as a sign of thanksgiving to God for having released the city of Milan from the plague. And in Turin it remained: until 1694 in the chapel of the Royal Palace, then inside the Cathedral, then in the Chapel of the Shroud built ad hoc within that apse. There it was kept until 1997 when, luckily retrieved from an arson, was placed again inside the Cathedral, where still now it is. In 1983 Humbert II of Savoy, the last King of Italy, donated it to the Holy See (source of point 1 was mostly from O'Connell's book).

(2) The hypothesis is plausible, though most is unclear of what happened to the linen cloth of Constantinople in the one-century and half period between its vanishing from the shores of the Bosporus and its appearance in France. To take it there has likely contributed the Burgundian Otto de la Roche sur-Ognon, Grandlord of Athens, "latin" commander of the District of Blacherne, where it was kept in St. Mary's church. He would have taken possession of the Shroud as war booty, is thought having sent it to his father as a present for the bishop of Besançon. Placed there in the cathedral of St. Etienne, it was exposed to the believers' veneration every year on the Holy Saturday until 1349, when a fire broke out. The casket with the relic, left luckily undamaged, vanished in the bustle of the event to emerge sometimes later in King Philip's VI hands. The requests of bishop to regain the Shroud were useless,, so, he ordered a painted copy - seemingly very similar to the original - in order to expose it to the believers' devotion in the same cathedral.

(3) Intresting, but little reliable is the Byzantine historian from the XIII-XIV century Nicephorus Xantopulo Callisto (ca 1256 - ca 1335) - and his Greek sources of the IV-VI century - in his book translated in Latin under the title Nicephori Callisti Xanthopuli scriptoris vere Catholici, Ecclesiasticae historiae libri decem & octo, Basileae per Ioannes Issi 1551, given at work by the translator. In the II volume, chapter VII, we read that the disciple Thaddeus, one of the Seventy, was sent to Edessa by the apostle Thomas to start preaching there the Gospel. Abgar V (also known as Agarus or Abgarus), the king of the city from AD 13 to 50, charged a skilled artist to go for Jesus and paint very carefully ("diligenter et accurate") his portrait and come back bringing the paiting. The artist went and standing in a high place he tried out his task, but couldn't, since the divine brightness and grace shining on Jesus' face prevented him from. Realizing it, the Saviour took a linen cloth with his own image already imprinted and sent it to Abgar. It was by sure a selfimpressed portrait ("picturam scilicet άυτόματον", the last word untranslated in the Latin text).

The features of Christ and of His Mother were taken also to the Persian King. It is in fact said, that he as well, moved by ardent faith, had sent a skilful painter to Jesus, who gave him a selfportrait and a portraite of his mother painted by himself. All these facts were deduced from documents and the archives of Edessa City, at that time ruled by a King. In volume XV, chapter XIII, we read: Pulcheria (399-453, sister of the emperor Theodosius II and she herself Roman Empress of the Orient after his death) founded the church of Blacherne to keep the image of Mary painted by the evangelist Luke. In chapter XXIII we find the mantle of the Virgin Mary laid in the round and spired church ("in rotundo atque acuminato templo") called Blacherne, in the city suburb bearing this name. Lastly, in chapter XVI, volume XVII, Edessa is described as marvellous ("mirifica") and by voice and people believe ("supra opinionem & fidem omnium") governed ("gesta"), by the image not made by men ("non manufacta") of Our Lord God and Saviour ("servatoris") Jesus Christ. The uneasy comparison of data and dates might suggest that the linen cloth or clothes kept for short time in Edessa had reached Constantinople already in the V century, that is half millenium before the year 944. In conclusion and with the due reservations on the authenticity of this text, it's difficult to believe that the "Edessa story" is bereft of any historic ground.

(4) The Edessians feared their relic might be destroyed by the orthodox Judeans, but also by Christians: first ones felt a deep repugnance against objects somehow related with corpses, while second ones although they were allowed to represent Jesus by the the Mystic Lamb, they weren't allowed to represent the signs of Passion and cross, still retained for centuries the symbol of an infamous death. It was only after the Council of Constantinople of 692 that on the cross appeared Jesus alive, whereas the dead Christ became commonplace only in the X century. But the worst hazard for the mandylion was at first represented by the Muslims who conquered the city in the VII century, and then by the iconoclastic fury of the VIII and IX centuries.

(5) Matthew, 27,59: So Joseph (from Arimatea) took the body (of Jesus) and wrapped it in a clean shroud (σινδόνι καθαρά) and put it in his own new tomb...

Mark, 15,46: And he (Josepf of Arimatea), bought a shroud (σινδόνα), took Jesus down from the cross, wrapped him in the shroud (σινδόνι) and laid him in a tomb...

Luke, 23,53: He (Joseph of Arimatea) then took it down, wrapped it in a shroud (σινδόνι) and put it in a tomb...

John, 19,40: They (Joseph of Arimatea and Nicodemus) took the body of Jesus and bound it in linen cloths (όθονίοις) with the spices, following the Jewish burial custom.

Luke, 24,12: Peter, however, went off to the tomb, running. He bent down and looked in and saw the linen cloths but nothing else (όθόνια).

John, 20,4-7: ("the other disciple") running faster than Peter, reached the tomb first; he bent down and saw the linen cloths (τά όθόνια) lying on the ground (κείμενα) ... Simon Peter, following him, also came up, went into the tomb, saw the linen cloths (τά όθόνια) lying on the ground (κείμενα), and also the cloth (τό σουδάριον) that had been over his head; this was not with the linen cloths (μετά των όθονίων), but rolled up (έντετυλιγμένον) in a place by itself.